Rafael Megall

Porselen İdoller - Çizgi Film Dilinde Kaos (Porcelain Idols - Chaos in the Language of Cartoons), 2021

Porselen İdoller - Denizciler (Porcelain Idols - Sailors), 2020

Porselen İdoller - Kayakçı (Porcelain Idols - The Skier), 2019

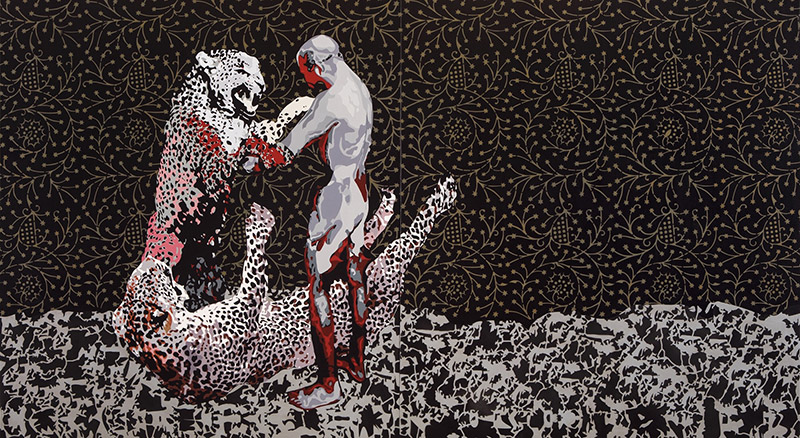

The Panthers in My Blossoming Garden - Game of Panthers (Çiçekler Açan Bahçemdeki Panterler - Panterlerin Oyunu), 2018

The Panthers in My Blossoming Garden #6-2 (Çiçekler Açan Bahçemdeki Panterler #6-2), 2018

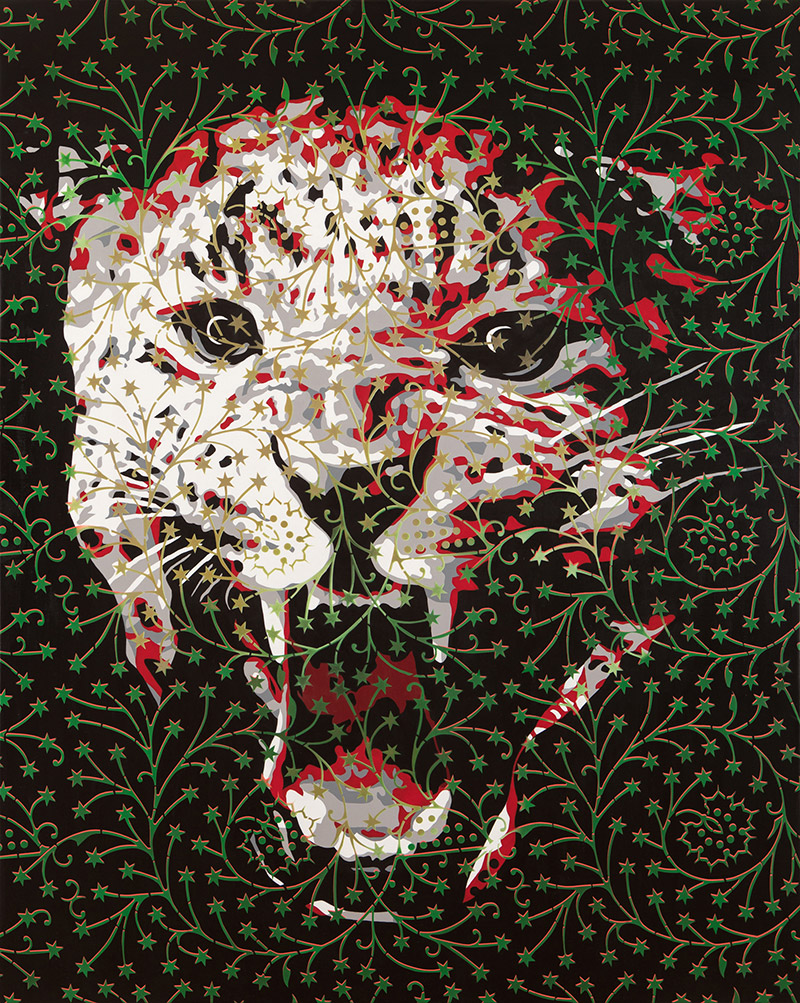

The Panthers in My Blossoming Garden - Head #2 (Çiçekler Açan Bahçemdeki Panterler - Kafa #2), 2018

Two-Headed Panther (Limited Editions 1/9) / Çift Başlı Panter (Sınırlı Edisyon 1/9), 2018

Biography:

Born in 1983, Yerevan, Armenia

1998-2004 Studied in Yerevan State Academy of Fine Arts

Since 2008 Member of the “Union of Artists of the Republic of Armenia”

Since 2010 he lives and works in Armenia and USA

Personal Exhibitions:

2017 The Panthers in My Blossoming Garden, National Gallery, Yerevan, Armenia

2017 The Panthers in My Blossoming Garden, 57th Venice Biennale, Pavilion of the Republic of Armenia, Venice, Italy

2015 Human Nature, Gallery In Arco, Turin, Italy

2012 Turn on Emotion, Artists` Union of Armenia, Yerevan, Armenia

2011 Born in Night, Contemporary Art museum, Yerevan, Armenia

2011 The Last Works, Gallery 8, London, UK

2010 Miniature, Artists’ Union of Armenia, Yerevan, Armenia

Group Exhibitions:

2018 Gender Fluidity, Haugar Vestfold Kunst Museum, Tonsberg, Norway

2018 The New Fronties of Painting, Fondazione Stelline Milano, Milan, Italy

2017 Seeing Whales, Galleria Mazzoli, Modena, Italy

2016 Paperwork, Galleria Pack, Milan, Italy

2015 The Divine and its Representation, A conference in occasion of the exhibit “The Shroud and its Imprint on the Art” curated by Demetrio Paparoni, Gallery In Arco, Turin, Italy

2015 3rd edition of Cramum Award for Contemporary Art, The Cramum Association and the Giorgio Pardi Foundation, Milan, Italy

2015 La Sindone e l`impronta dell`arte (The Shroud and its Imprint on the Art), Municipal Museum of Sansepocro, Arezzo, Italy

2014 Dublin Biennale, Dublin, Ireland

2013 Florence Biennale, Florence, Italy

2012 Salon d`Automne, Paris, France

2011 Florence Biennale, Florence, Italy

2011 Broadway Gallery, NY, USA

2011 Armenian Contemporary Art, Museum of Contemporary Art, Kuwait

2010 National Gallery, Yerevan, Armenia

2009 Florence Biennale, Florence, Italy

2009 Sofa New York, USA

Rafael Megall was born on 2 January 1983 in Yerevan. He started to paint when he was 9 years old. Between 1998 and 2004, he studied in Yerevan State Academy of Fine Arts. Since 2008 he is member of the Union of Artists of the Republic of Armenia. Since 2010 he lives and works in Armenia and USA. Starting from 1995, he has had numerous individual expositions, as well as has participated in a number of international exhibitions.

In 2012 he received Gold Medal of the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Armenia for his services and achievement. In 2013 the President of Armenia gave him the honorary title of “Honored Artist of the Republic of Armenia”. In 2013 Florence Biennale IX Edition he received The Lorenzo il Magnifico Award in the category of "painting". In 2014 he granted the "Arshil Gorky" honorable Medal of Republic of Armenia.

Review:

"The Panthers in My Blossoming Garden"

Rafael Megall’s work confronts the complex relationship between man and nature. In considering man and nature as mirror images of each other, Megall deals with their relationship in terms of complementariness despite their latent reciprocal threat.

A central theme of the works created by Megall for the Armenian Pavilion of the 57th Venice Biennale is the presence of elegant and aggressive panthers immersed in colorful and blossoming nature. In these paintings the artist emphasizes how it is behind the beauty assumed by the feline while in his natural habitat that the danger of his aggression hides. The title of the exhibit, “The Panthers in My Blossoming Garden”, highlights the constant presence of danger for man, even when he feels safe within the boundaries of his environment. Yet, it also represents the danger animals face because of man. Megall, therefore, turns the panther into a metaphor of the threat that can hide behind an image of beauty, while using lush nature as an allusion to lost paradises.

The colors of the landscape, presented in sharp, electric and vibrant segments, produce contrasts that recall the saturation of a digital image. In order to emphasize this visual effect and to adapt it to the language of painting, in addition to acrylics, Megall uses watercolors, which lighten as they absorb and expand the colors through moist sifts. The expedient creates an out-of-focus effect, which causes the colors of the animal and those of the plants to blend, giving life to a unique body. While, in a sense, the psychedelic effect that, in these works, derives from the combination of these colors and from their saturation alludes to the idealism of the Sixties and the dream of finding a place where it is possible to live in harmony with nature, the dense and redundant intertwining of the decorations that permeate the canvas produce a visual noise that prevents the landscape to be perceived as an oasis of peace.

In these paintings one can perceive the echo of the transformation of natural elements into decorative frames, which in Armenian ancient miniatures and bas-reliefs take shape through stylization, repetition, linkages and interlaces. The resonance of this historical memory becomes particularly evident in the continuous references to “khachkar”, bas-reliefs on stone steles bearing carved crosses featuring two blooming sprouts at their base, a motif that also characterizes his previous paintings. At the same time, the overlapping of linguistic elements of a different nature eliminates any nostalgic connotation to past artistic experiences. While allusion to Medieval illuminations is not entirely preserved due to the scale of the canvases, reference to the bestiary, which is responsible for the less than realistic apperance of the animals, assumes a more pivotal relevance. Like the authors of medieval bestiaries, Megall is not able to account for nature without considering the spiritual dimension: his paintings reveal themselves as a sort of ciphered text in which the figures refer to the complex happenings of the present.

Megall uses a method that, in its initial phase, involves the digital elaboration of different studies on the canvases through a technique that includes the use of masks. The digital approach, along with flat surface painting, saturated colors and the absence of perspective, are testimony that the work follows an analysis of the painter’s instruments. Once on the canvas, the outlines and the colors of the original image are subjected to continuous modifications. It is, therefore, not the narrative which transforms, but rather the arrangement of colors and the incisiveness of the markings.

In the preliminary phase, the narrative is constructed by associations of symbolic elements and, when present, references to the conctreteness of the day-to-day. In some works, the subjects related to the artist’s day-to-day are his family and the Italian mastiffs that live in the backyard. In others, the narrative extends to the menacing events of the present that reawaken old fears.

Between April and May of 2016, shortly before initiating work on the series “The Panthers in My Blossoming Garden”, Megall created a large scale painting that depicts the forces of evil. The work, entitled “Lucifer”, revisits an ancient Armenian illumination by showing a large serpent among flames that devours a man and envelops other victims in its coil. In the image, the devil resembles the serpent that introduced evil in the Garden of Eden. Megall makes customary references to zoomorphic and phytomorphic elements present in Armenian art, using them in both a narrative and decorative fashion. In the case of “Lucifer”, the genesis of the work finds its raison d’être in the aftermath of the tragedies of the dispute over the Nagorno Karabakh region. Drawing from the emotions elicited by these events, “Lucifer” is the artist’s interpretation of the reawakening of the evil forces of war. In creating this work, Megall also used volcanic soil from Mount Ararat, which continues to represent the symbol of cultural identity for the Armenian People.

The idea of the forces of evil that are insinuated among us by assuming the appearance of a serpent returns in “The Panthers in My Blossoming Garden 8 (The Panther Snake)”, in which a panther seen from above, and blended in with the nature that surrounds it, assumes the appearance of a serpent with a feline head that is ready to attack. While, on the one hand, the concealed animal recalls danger and ambush, on the other, it transmits the sense of unity in nature.

The repetition of shapes that composes a unitary image, resembling modules to be placed in different manners, allows Megall to aquire a constructive method which, while it may appear paradoxical when considering the accumulation of signs and the figurative and decorative component of his works, also derives from the minimalist experience of Donald Judd. Megall looked to Judd’s constructive method, whose work he became familiar with in various publications from 2004, when, at twenty one years of age, he attended the Yerevan State Academy of Fine Arts. His attention was drawn to the way in which the American artist distributed modular shapes in space which, thanks to variations in arrangement, allowed for the attainment of different wholes, despite using the same geometric modular volumes. A symbolic-narrative transposition of the concept of the modular element can be observed in panther paintings #2 and #6.

Narrative, symbolic and fantastical, Megall’s work does not look to the fact of nature in order to insert it in his work as an element of scientific truth. And yet, as in the modernist tradition, it emerges as an analytic study of language in art. Moreover, by mirroring the spirit of time, it reflects the condition of an artist who is aware of the impossibility of giving life to works that can be considered original, innovative and revolutionary at a linguistic level. These paintings betray both historical allusion and the progressive logic of those who maintain that art must manifest a character of originality and of uniqueness.

“The Panthers in My Blossoming Garden #7 (Totem)” depicts a panther standing up on its back legs, with its front legs crossed. Its posture makes for an anthropomorphic figure. A lattice of flower-shaped crosses covers the entire scene, acting as a background and at the same time superimposing itself on the subject. This hieratic figure is a sort of counterbalance to “Devil” (2015), another painting by Megall that illustrates the forces of evil. “Devil” exhibits a close-up of the threatening face of a being that is half-man, half-animal, whose nature is undefined. In other works of the series “The Panthers in My Blossoming Garden” (specifically #10, #11 and #12), the title is completed by the phrase “The mouth of truth”. What truth are we brought before by the open mouth of an animal showing its teeth? And what truth are we placed before by the same bleeding animal? (“Sacrificial Victim”, pain- ting #3). By gathering big cats within an enclosure that is rich with vegetation and memories, Megall reiterates that the way in which we confront cohabitation and exchange, both today and yesterday, manifests itself in art. It could not be any other way. It is the absence of a common language that divides us from others. Art, on the other hand, is a univeral language. It aspires to be understood by all, and to shatter the barriers that make us into unsettled people by separating us.

Demetrio Paparoni, Art Critic

57th Venice Biennale Pavilion of the Republic of Armenia, 2017

“The artist and his Mother”, Installation at The National Gallery of Armenia, 2017

When you set out to describe the most painful moments experienced by your people through the language of art, the figures and the symbols you make reference to must be the highly expressive and significant. There are brilliant works in this sense. In literature there is “The Unstoppable Bell Tower” by Paruir Sevak, in architecture there is “The Memorial” by Dzidzernagapert, in music there is “Komitas”, in painting there is “The Artist and His Mother” by Arshile Gorky.

I drew inspiration from the painting by Gorky and its title for the installation made for my exhibition at the National Gallery of Armenia. In my installation the artist evoked in the title is not only the young Gorky, but the many young people (and old) who lived as refugees. The mother, with signs of pain etched on her face, becomes the mother of every Armenian. Here Gorky’s painting has been reduced to shreds by “Two-Headed Panthers”. The installation represents a sacrilege: man is the perfect creature created by God, hence destroying a painting that depicts him is a sacrilege that surpasses the act of vandalism. These panthers represent evil as such. They are ravenous animals, yet their dark colors and the way in which the surface is handled make them, in some way, captivating: evil has an alluring power, this is well-known. And it is this very alluring power that must be defeated.

At their feet, there is a classic Armenian rug, red as blood. The white superimposed decor expresses the hope for change.

Rafael Megall, Yerevan 2017